IOL Exchange

IOL Exchange is used on those rare instances that the patient fails to adapt to multifocal lens with debilitating quality of vision, glare, ghosting etc. It is not a routine surgery, involves more intraocular manipulation and thus becomes a more risky procedure than the original surgery. With patients having increasingly high expectations for their vision and spectacle independence, choosing the right intraocular lens for the right patient can be a challenge. No matter how thorough the patient education and how precise the lens calculations, at times the IOL can be mismatched to the patient. In this situation, an IOL exchange may be the best option to deliver satisfaction and good vision to the patient.

Patient Expectations

In the majority of potential IOL exchange candidates, the original lens was likely an appropriate choice but perhaps didn’t meet the patient’s expectations. Make sure that the patient does not have unrealistic expectations, a goal of ‘perfect’ vision, or a mindset of finding the fountain of youth. Any additional surgical procedure such as an IOL exchange has higher risks than the original surgery: additional incisions in the eye which can affect astigmatism and healing, further potential for corneal endothelial cell loss, and a repeat exposure to the risks of endophthalmitis and retinal complications. The most important risks that IOL exchange patients face are rupture of the capsular bag and development of cystoid macular edema. Patients need to be patient with the postop recovery, which can be prolonged when compared to routine cataract surgery, and they need to understand that if their capsular bag breaks during surgery, they may receive a different IOL than originally planned.

Preoperative Evaluation

If the first IOL was compatible with the patient’s expectations but just resulted in a refractive error, then a simpler procedure, such as a piggy-back IOL or an excimer-based corneal ablation, may be the better choice. If, however, the patient has received an IOL design that he cannot longer tolerate, such as a multifocal IOL or a blue-blocker IOL, then an IOL exchange is the more suitable procedure.

IOL calculations are critical and every attempt to get the records of the first surgery should be made, as knowing the power of the original IOL and the resultant postop refraction will allow for a more precise selection of the new IOL. If the patient has significant cylinder, then incision placement or additional relaxing incisions or the implantation of a toric lens can be employed to reduce the amount of astigmatism.

On microscopy the amount of capsular fibrosis, the size and shape of the capsulorhexis, the type of IOL used, and the position of the incisions can assist with the surgical planing and risk assessment. Hydrophobic acrylic IOLs tend to be more adherent to the capsular bag than IOLs made from other materials, and as such, they can be more difficult to dissect free.

Medications

Preoperative treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or a combined antibiotic/steroidal is important for four reasons: 1) prevention of intra-operative miosis; 2) analgesia and patient comfort; 3) reduction in the postop inflammatory response; and most importantly, 4) prevention of postop cystoid macular edema. Because of the additional trauma induced during the second surgery, use of an NSAID can play an important role in preventing postop CME, which would otherwise significantly limit vision. I like to have the patients use the NSAID for two full months, so having a drop that is dosed just once or twice a day is more advantageous, particularly when it is very potent and has the ability to penetrate long, myopic eyes.

Surgical Technique

I tend to perform these cases under subtenons anesthesia, as well as intravenous systemic sedation by an anesthesiologist. Fill the anterior chamber with a cohesive viscoelastic to keep it formed during the surgery. Next, use a more dispersive viscoelastic on a LASIK flap lift blunt canula. Canula is placed under the capsulorhexis edge, inject to perform viscodissection. Next, use a blunt spatula to fully dissect the anterior capsule free from the IOL. Making a second paracentesis opposite from the first one is helpful, allowing a full 360 degrees of access.

By injecting viscoelastic under the IOL optic, the capsular bag can be safely dissected and separated from the acrylic lens surface. Once there is some protection of the posterior capsule, the blunt viscoelastic can be used to gently lift the IOL. The chopper or second instrument can then be used to dial the IOL out of the capsular bag and into the anterior chamber.

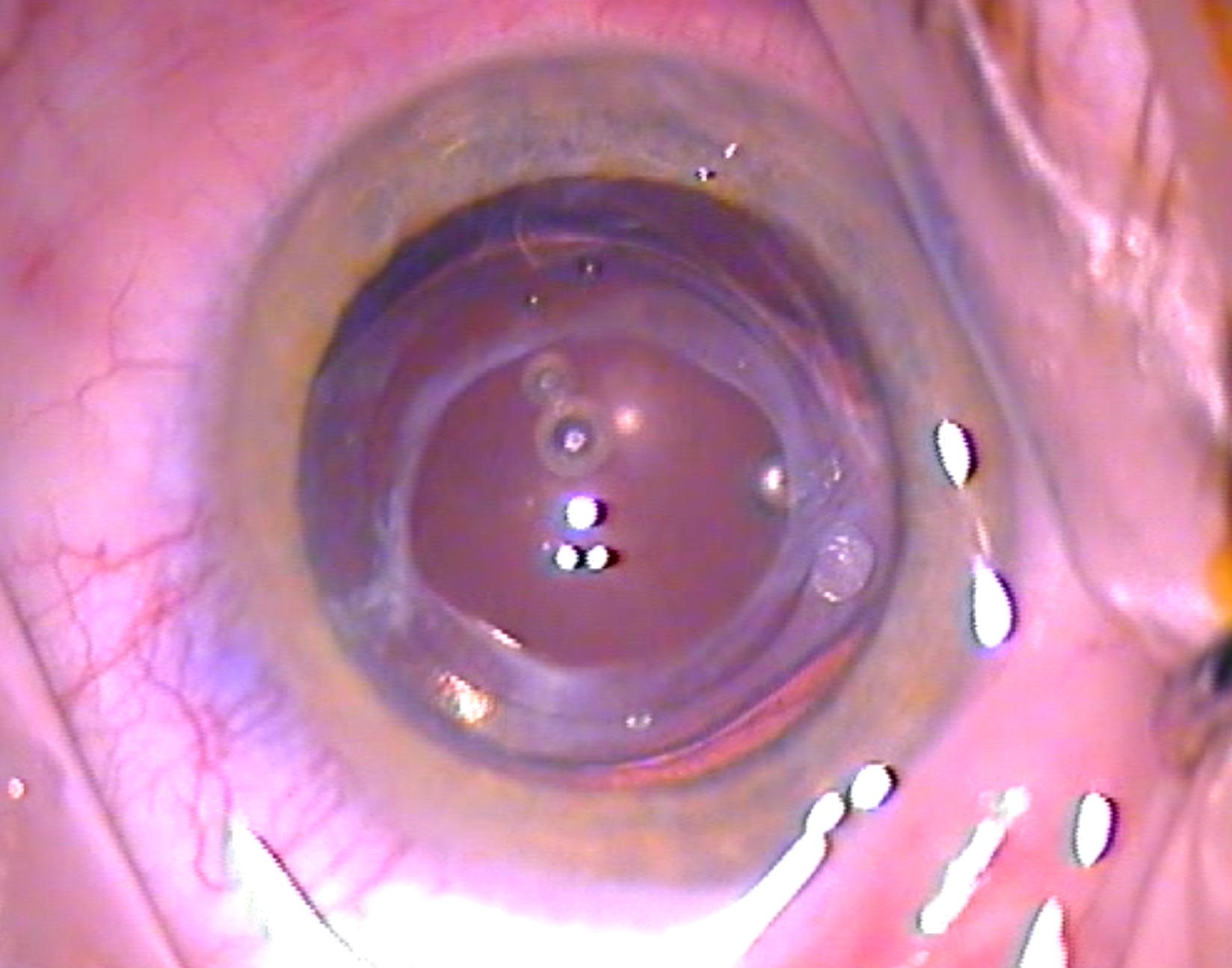

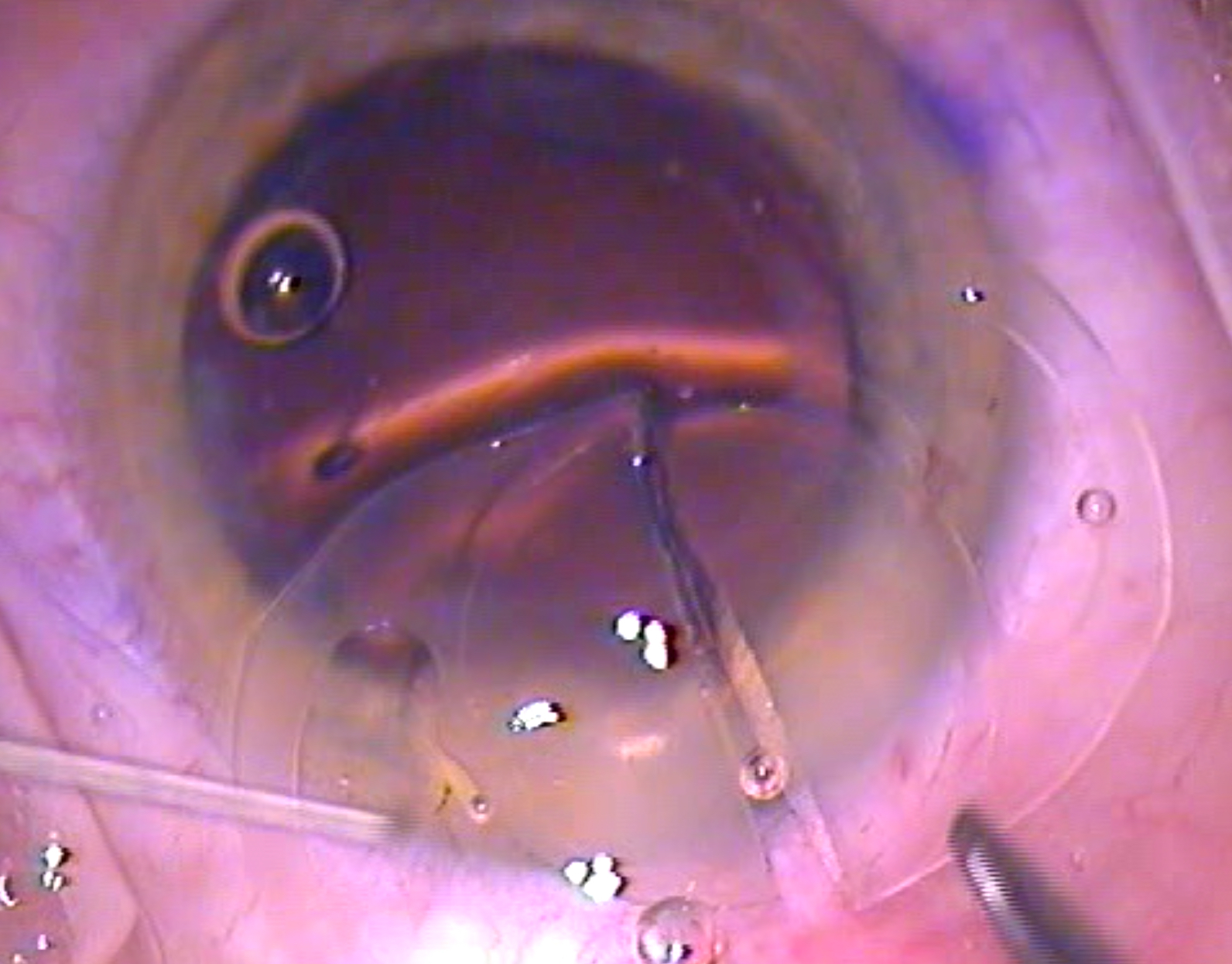

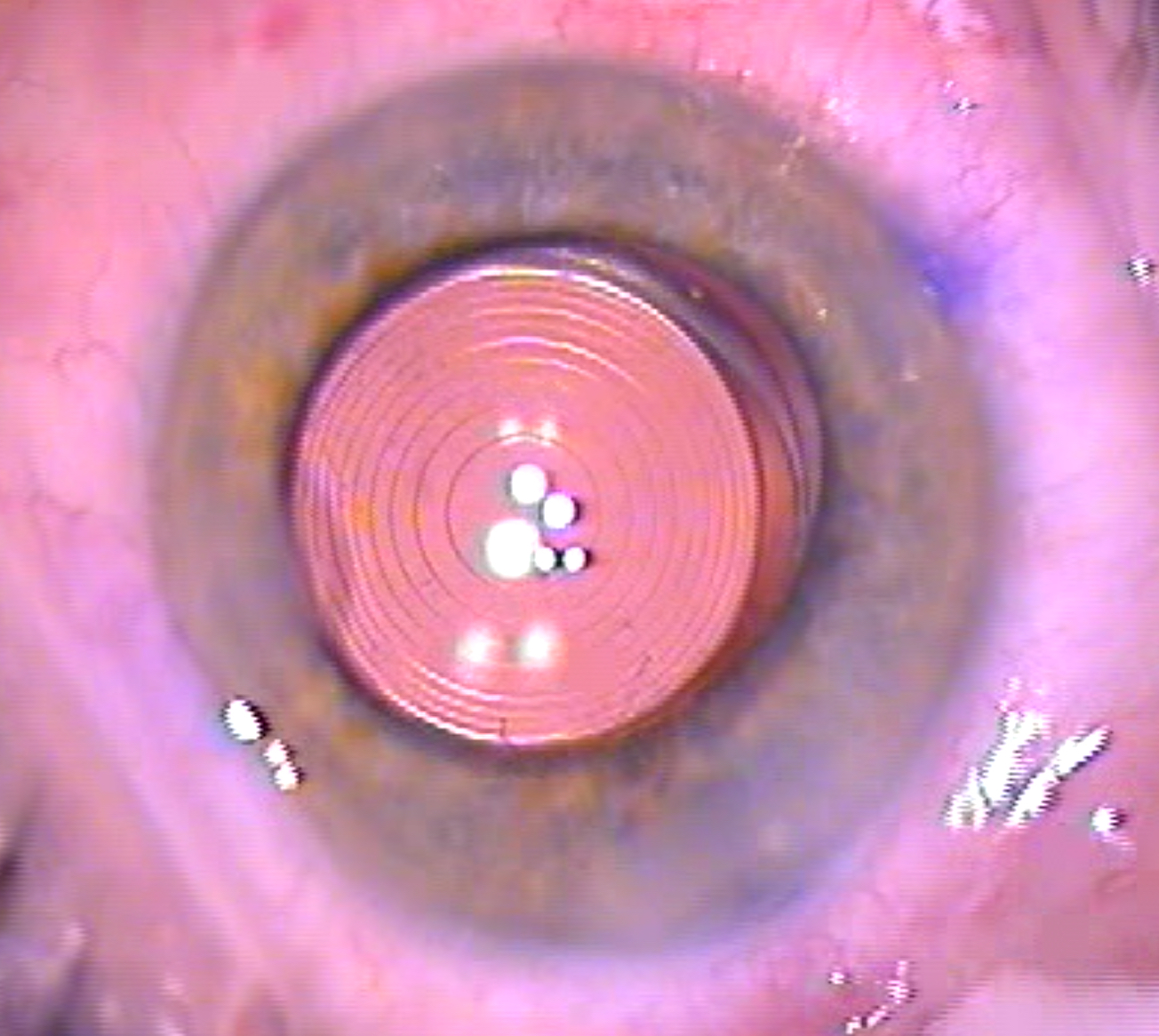

Once the original IOL is in the anterior chamber, bring it up towards the corneal endothelium. The previously injected viscoelastic will be a good barrier to protect the corneal endothelium. At this point, some surgeons like to remove the original IOL before placing the new IOL and others to implant the new lens first before cutting and removing the old lens. The lens is manipulated out by the use of special instruments like the MST micro-forceps and micro-scissors through the original incision. At this point, the viscoelastic can be removed and the incisions can be secured. Below you can see an opacified multifocal IOL 4 years after original surgery with advanced fibrotic reaction in the capsule leading to anterior capsular phymosis; on the second picture the IOL is now cut and out of the eye; on the third picture the new multifocal IOL is perfectly centred within the now clear capsule and enlarged new capsulorhexis. The patient was very happy with the result.

Risks

Visual outcomes after IOL exchange can be excellent, but again, surgery carries many risks. Anterior vitrectomy is the most common intraoperative complication, noted in up to 85% of PCIOL explantations(1). A more recent study reported a lower rate of 33.3%, but that number is not insignificant(2). The risk is greater in patients with an open posterior capsule such as those who have undergone an Nd:YAG posterior laser capsulotomy(3). Another common complication is zonular dehiscence, noted in up to 44% of IOL exchanges(4).

To remove a PCIOL from the capsular bag, most surgeons use intraocular scissors to fragment the IOL and then remove the pieces. In order to prevent trauma to the zonules, some ophthalmologists remove only the optic and leave behind the haptics, because they may be adherent to the capsular bag(5). These haptics, however, can dislocate into the optical axis or vitreous, or they can interfere with the position of the new IOL. Surgery to reposition or exchange an IOL that has dislocated into the vitreous cavity requires concurrent pars plana vitrectomy and carries numerous risks, including postoperative cystoid macular edema and retinal detachment(6).

It is generally preferable to implant the replacement IOL in the capsular bag. If this is not possible, the new IOL can be placed in the sulcus or anterior chamber. Scleral fixation of a PCIOL is also possible. It carries the risk of suture rupture with subsequent IOL dislocation, retinal detachment, and ocular hypertension, however, and is associated with a high rate of additional surgery(7). Although less common with modern designs, there are still complications related to the placement of an anterior chamber IOL such as pseudophakic bullous keratopathy(8).

Postoperative Management

The slightly prolonged surgical time (8 to 16 minutes) and intraocular manipulation can cause more inflammation and make for a longer postop recovery. To help with the inflammation and to speed visual improvement, I use a strong steroid in addition to an NSAID. Prednisolone acetate 1% is prescribed four times a day for three weeks, and Ketorolac Trometamol 0.5% (Acular) is prescribed q.i.d. for six weeks. This ensures that the inflammation is fully resolved, the postop discomfort is eliminated, and the risk of cystoid macular edema is reduced.

Because of the extra incisions, opening prior incisions, and the re-operation, there may be a higher risk of incision leakage, and therefore infection, after surgery. Use of a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone is highly recommended both before and after surgery. Aims for the antibiotic is a fast kill time and a full spectrum of microbial coverage, and we select Oftaquix (levofloxacin).

Typically 6 weeks after the surgery a repeat dilated fundus examination is performed in order to search for possible retinal breaks or weakness that may have been created during surgery as well as to monitor the macula for signs of edema.

An IOL exchange surgery can be challenging due to the increased risks and higher degree of technical intricacy, but it can provide a remedy for patients when the original IOL does not meet their expectations. Patient education and information about the nature and details of the surgery along with a sound surgical plan with appropriate lens selection and postop follow up is the mainstay of successful management of IOL exchange.

References:

- Marques FF, Marques DM, Osher RH, Freitas LL. Longitudinal study of intraocular lens exchange. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33(2):254-257.

- Jones JJ, Jones YJ, Jin GJ. Indications and outcomes of intraocular lens exchange during a recent 5-year period. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(1):154-162 e151.

- Leysen I, Bartholomeeusen E, Coeckelbergh T, Tassignon MJ. Surgical outcomes of intraocular lens exchange: five-year study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35(6):1013-1018.

- Dagres E, Khan MA, Kyle GM, Clark D. Perioperative complications of intraocular lens exchange in patients with opacified Aqua-Sense lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30(12):2569-2573.

- Lee SJ, Sun HJ, Choi KS, Park SH. Intraocular lens exchange with removal of the optic only. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35(3):514-518.

- Sarrafizadeh R, Ruby AJ, Hassan TS, et al. A comparison of visual results and complications in eyes with posterior chamber intraocular lens dislocation treated with pars plana vitrectomy and lens repositioning or lens exchange. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(1):82-89.

- McAllister AS, Hirst LW. Visual outcomes and complications of scleral-fixated posterior chamber intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(7):1263-1269.

- Lyle WA, Jin JC. Secondary intraocular lens implantation: anterior chamber vs posterior chamber lenses. Ophthalmic Surg. 1993;24(6):375-381.